By Nick D.

Since World War Two, every revolution successful in overthrowing capitalist rule has taken place in societies outside the imperialist core. In the coming period, there is every chance that the Global South – home to a large majority of the world’s population – will again be the site of the next revolutionary seizure of power.

It is therefore important to reflect on the general character of revolution in Global South countries, where social realities – in particular the social weight of non-proletarian classes – are distinct compared to industrially advanced, imperialist economies such as Australia.

The Bolshevik Revolution provided a powerful example of strategy for socialist revolution in colonial and semi-colonial countries with large non-proletarian populations.

According to Lenin’s theory – which was developed in the 1905 Revolution and historically confirmed in the 1917 Revolution – the process of socialist revolution in such countries will likely proceed in two distinct phases: the democratic stage and the socialist stage.

This talk will explain the core theoretical tenets of Lenin’s two-stage theory of revolution and outline its realisation in the Bolshevik Revolution. It will also argue that socialists in imperialist countries need a firm understanding of the process and realities of Global South revolution in order to best respond when a revolutionary crisis emerges.

A sectarian ultra-left perspective – that chastises Global South revolutionaries stuck in the first stage of revolution due to domestic and international conditions – both undermines support and solidarity with Global South revolutions and prevents revolutionaries overseas from developing a clear-eyed analysis of the modern imperialist system.

A Very Brief Definition

Speaking about Lenin’s 1905 work, Two Tactics of Social-Democracy in the Democratic Revolution, Vijay Prashad remarks,

“Two Tactics is perhaps the first major Marxist treatise that demonstrates the necessity for a socialist revolution, even in a ‘backward’ country, where the workers and the peasants would need to ally to break the institutions of bondage”.

As Prashad indicates, the Bolshevik’s revolutionary strategy for an ‘industrially backward’ country like Russia depended on forging an alliance between the workers and peasantry – which would be led by the former.

Based on this alliance, the socialist revolution would first pass through the ‘bourgeois’ stage referred to by Lenin as the “revolutionary-democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry”. The specific reason why this is a ‘bourgeois’ stage is that it is centrally hinged on non-socialist tasks, in the case of Russia, the agrarian revolution.

Menshevik and Bolshevik Tactics in 1905

The origins of Lenin’s two stage theory of revolution lie in the 1905 Revolution. During this time, both wings of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) – which was divided into the Mensheviks (minority) and Bolsheviks (majority) – agreed on the main task of the revolution in Russia: overthrow the Tsarist autocracy.

The Mensheviks, however, argued that the Russian proletariat was too weak to play an independent role in the revolution. In backwards Russia, they argued, there needed to first be a sustained period of capitalist development which would increase the size and strength of the proletariat. This would open the possibility – many years in the future – of socialist revolution in Russia.

Given the relative weakness of the proletariat, Menshevik leaders like Georgi Plekhanov, Alexander Martynov and Julius Martov asserted that the revolution should be led by the anti-Tsarist liberal-bourgeois opposition. The Menshevik newspaper, Iskra, wrote in 1905 that the role of the proletariat was to support the liberal bourgeoisie:

“We must encourage it, and on no account frighten it by putting forward the independent demands of the proletariat” (Quoted in G. Zinoviev, History of the Bolshevik Party: A Popular Outline).

According to this view, the proletariat movement needed to push the Russian bourgeoisie to support reforms that favoured the working class, such as the eight-hour day, but must submit to its leadership and do nothing to frighten it – i.e., anything that strengthens the workers. This was emphasised by Martynov in his 1905 pamphlet Two Dictatorships:

“…the revolutionary struggle of the proletariat, by simply frightening the majority of the bourgeois elements, can have but one result—the restoration of absolutism in its original form …” (Quoted in V.I. Lenin, Social Democracy and the Provisional Revolutionary Government).

The Mensheviks vehemently opposed attempts to seize power and argued that socialists should focus on organising workers in economic struggles while leaving political struggle to the liberal bourgeoisie. At a Menshevik conference held in 1905, a resolution was passed:

“Only in one event should Social-Democracy, on its own initiative, direct its efforts towards seizing power and holding it as long as possible—namely, in the event of the revolution spreading to the advanced countries of Western Europe, where conditions for the achievement of Socialism have already reached a certain degree of maturity.” (Quoted in V.I. Lenin, Two Tactics of Social-Democracy in the Democratic Revolution).

For the Bolsheviks, the central task of the working class in 1905 was to carry out a bourgeois-democratic revolution against the Tsarist autocracy. In other words, the proletariat should lead a popular revolution to eliminate feudalism and tsarism, but one which does not immediately “destroy the foundations of capitalism”.

Crucially, in the Bolshevik formulation, the bourgeois revolution would not be led by the bourgeoisie but the proletariat in alliance with the peasantry. In Two Tactics, Lenin maintained that in general, the Russian bourgeoisie was too fearful of the popular classes and too linked to tsarism to play a truly revolutionary role:

“It is of greater advantage to the bourgeoisie if the necessary changes…as little as possible the independent revolutionary activity, initiative and energy of the common people, i.e., the peasantry and especially the workers, for otherwise it will be easier for the workers, as the French say, “to hitch the rifle from one shoulder to the other,” i.e., to turn against the bourgeoisie the guns which the bourgeois revolution will place in their hands, the liberty which the revolution will bring, the democratic institutions which will spring up on the ground that is cleared of serfdom.”

Rather than tail-ending the bourgeoisie, the Bolsheviks argued that the proletariat needed to take a leading role in the revolution and unite with the peasantry. Through an alliance of “millions of urban and rural poor”, Lenin asserted that the Tsarist autocracy could be overthrown and replaced with a “revolutionary democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry”. In his 1909 article The Aim of the Proletariat in Our Revolution Lenin writes of the worker-peasant alliance:

“Our Party holds firmly to the view that the role of the proletariat is the role of leader in the bourgeois-democratic revolution; that joint actions of the proletariat and the peasantry are essential to carry it through to victory; that unless political power is won by the revolutionary classes, victory is impossible.”

In concrete terms, the “revolutionary democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry” consisted of a provisional revolutionary government based on the power of the exploited classes in Russia which together could complete the tasks of the bourgeois revolution. These consisted of, for example, the establishment of a democratic republic, land reform, separation of the church and state, full political liberties, economic reform etc.

In his writings during 1905, Lenin continually emphasised that this impending revolution would not be a socialist revolution. In Two Dictatorships, Martynov had asserted that socialists must not participate in a potential provisional government because, once in power, the “party of the proletariat” would have no choice but to “put our maximum programme into effect, i.e., …bring about the socialist revolution”. In The Revolutionary-Democratic Dictatorship of the Proletariat and the Peasantry, Lenin responded:

“This argument is based on a misconception; it confounds the democratic revolution with the socialist revolution, the struggle for the republic (including our entire minimum programme) with the struggle for socialism. If Social-Democracy sought to make the socialist revolution its immediate aim, it would assuredly discredit itself…For this reason Social Democracy has constantly stressed the bourgeois nature of the impending revolution in Russia and insisted on a clear line of demarcation between the democratic minimum programme and the socialist maximum programme.”

The reason why social democracy would “discredit itself” by attempting to carry out a socialist revolution in the first instance was because the possibility of the proletariat actually winning and then retaining political power – in the face of the inevitable attempts at counter-revolution – depended on its ability to head a popular revolution i.e., one involving the mass of the population:

“…If the Russian autocracy…is not only shaken but actually overthrown, then, obviously, a tremendous exertion of revolutionary energy on the part of all progressive classes will be called for to defend this gain.” (V.I. Lenin The Revolutionary-Democratic Dictatorship of the Proletariat and the Peasantry).

It was therefore crucial for the revolutionary proletariat to win over the peasantry – roughly 66% of the population – who above all wanted equal tenure of land and the complete destruction of feudalism – both of which are not socialist measures in that they can be carried out within the bounds of the capitalist social system. Lenin wrote:

“…the peasantry…is capable of becoming a wholehearted and most radical adherent of the democratic revolution…for only a completely victorious revolution can give the peasantry everything in the sphere of agrarian reforms—everything that the peasants desire, of which they dream, and of which they truly stand in need…” (V.I. Lenin, Two Tactics).

A crucial aspect of the Bolsheviks theory is that the first and second stages are not separate, but rather must proceed ‘uninterruptedly’. Lenin continues:

“…from the democratic revolution we shall at once, and precisely in accordance with the measure of our strength, the strength of the class-conscious and organised proletariat, begin to pass to the socialist revolution. We stand for uninterrupted revolution. We shall not stop half-way…we can and do assert only one thing: we shall bend every effort to help the entire peasantry achieve the democratic revolution, in order thereby to make it easier for us, the party of the proletariat, to pass on as quickly as possible to the new and higher task—the socialist revolution.”

The speed at which this socialist stage could begin depended on the level of class consciousness and organisation of the masses and the ability of the revolution to provoke uprisings in other countries. As quoted above, it would also depend on the speed at which differentiation occurs within the peasantry, in particular between the poor, semi-proletarian elements of the peasantry, the middle peasants and rich peasants or rural bourgeoisie.

In ‘Left-Wing’ Communism: An Infantile Disorder, Lenin famously described the 1905 Russian Revolution as the “dress rehearsal” without which “the victory of the October Revolution in 1917 would have been impossible”.

Although it failed to overthrow the Tsar and was ultimately crushed, the 1905 Revolution provided revolutionaries with a number of crucial lessons. These included the importance of the general strike as a tactic and the Soviet as an embryonic form of worker’s government. It also saw the development of the tactical approach of carrying out the revolution in two stages.

In Russia, the tactics of a proletariat-peasant alliance completing the democratic revolution and proceeding to the higher, socialist stage of revolution were realised eight months after the October Revolution, during the summer and autumn of 1918.

The February and October Revolutions

On February 23, 1917 (old calendar), the International Women’s Day march in Petrograd began. Two days later, a general strike swept across Petrograd. On March 2 Tsar Nicholas II abdicated and the Provisional Government was formed.

The February-March Russian Revolution was a democratic revolution that saw state power transferred from the feudal landed nobility headed by the Tsar to a capitalist-landlord government. In terms of formal, political rights, the Russian Republic was perhaps the most liberal of the imperialist countries in Europe given the limitations on political freedoms accompanying the First World War.

As a result of the revolution, a very unusual situation arose. On February 27 (old calendar) – before the Tsar had abdicated – the Soviet of Workers and Soldiers Deputies was formed in Petrograd. Politically, therefore, a situation of dual power developed in Russia. A dictatorship of the proletariat had been established, but it was subservient to the bourgeoisie. In his Letter on Tactics, Lenin wrote:

“We have side by side, existing together, simultaneously, both the rule of the bourgeoisie [the Provisional Government] …and a revolutionary-democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry [the Soviet], which is voluntarily ceding power to the bourgeoisie, voluntarily making itself an appendage of the bourgeoisie.”

The Bolshevik Party’s approach – particularly after the return of Lenin from exile and the subsequent adoption of the April Theses – was to carry out systematic revolutionary agitation amongst the proletariat and peasantry. Their central demands included the immediate end of Russia’s involvement in the war, distribution of land to the peasantry and transfer of the “entire power of the state to the Soviets of workers deputies”.

Through the slogan “Peace, Land and Bread!”, the Bolsheviks won mass popular support. They remained completely and uncompromisingly opposed to the Provisional Government and continually emphasised that it was a bourgeois-landlord government not capable of carrying out the tasks of the democratic revolution.

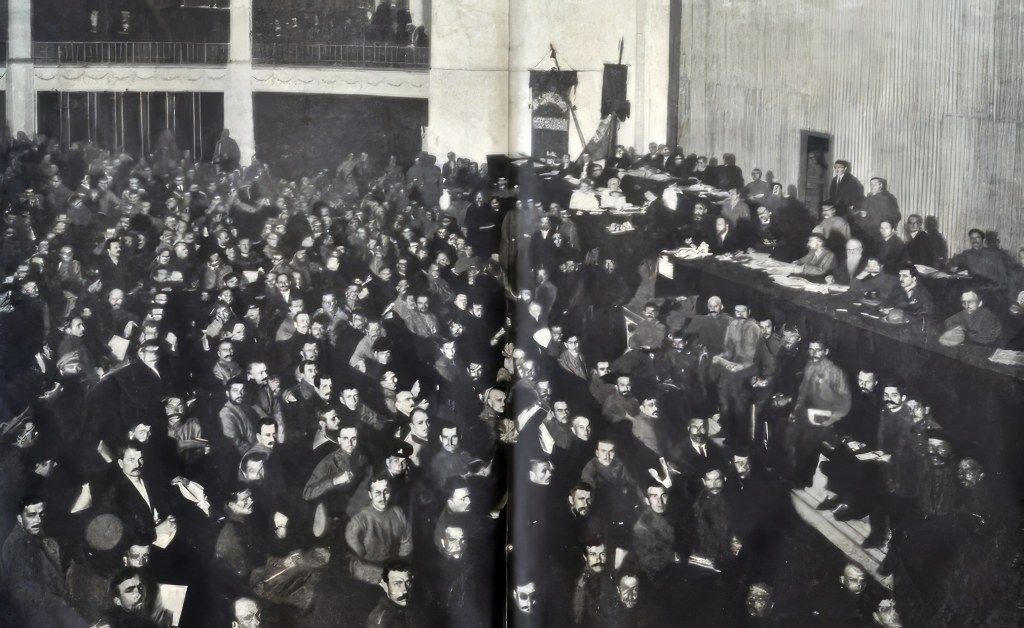

In the second half of 1917, Bolshevik tactics proved more and more successful while the situation continually turned in their favour. In the first months of the February Revolution, the Bolsheviks were in the minority of most Soviets. At the first All-Russian Congress of Soviets in June for example, the Bolsheviks had only 105 of 822 delegates.

By August and September, they began to win majorities in Soviets and won increasing support among the peasantry. By September, the Bolsheviks occupied up to 90% of the seats in the Petrograd Soviet and up to 60% in the Moscow Soviet.

The October Revolution began on November 6 (new calendar) and by November 8, the Winter Palace had been captured. At a meeting of the Petrograd Soviet, Lenin declared the victory of the “workers and peasants revolution”.

The October Revolution resolved the issue of dual power and saw the transfer of state control to a workers and peasants government. This was done at the second session of the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies and in January 1918 the Constituent Assembly was dissolved.

Having won state power, the Russian proletariat set about carrying out the democratic tasks that the bourgeois-landlord government – that came into power in February 1917 – was unable to fulfil. In this sense, the immediate task of the October Revolution was to begin and then complete the bourgeois-democratic stage of the revolution and proceed uninterruptedly to the socialist stage.

From the First to the Second Stage of the Revolution

When the Bolsheviks took power in October/November 1917, they faced a situation in which the industrial proletariat represented a minority of the population. According to 1913 statistics, the population of the Russian Empire was 170 million – 66% or 112 million of which were peasants.

For comparison, the industrial proletariat – i.e., workers employed in factories, mills, mines and smelters – numbered only 2.5 million. The peasantry was further divided into:

- Poor peasants: 73 million or 65% of all peasant families

- Middle peasants: 22 million or 20% of all peasant families

- Rich peasants: 17 million or 15% of all peasant families

At the same time, there were 28,000 landed aristocrats – the landlord class – with holdings equivalent to 10 million peasant families combined. The average holdings per landlord was 2,300 hectares. In comparison, 70 million peasants – 14 times the 2022 population of Melbourne – owned either little or no land at all.

All sections of the peasantry in Russia above all wanted the dispossession of the landlords, redistribution of the landed estates, equal land tenure and the complete destruction of feudalism. The Bolsheviks – now in power – understood this reality. They also understood that without the backing of the peasantry it would be impossible to retain political power.

Furthermore, in the first months of the revolution, class consciousness among the lower levels of the peasantry remained low and there had not emerged differentiation among different sections of the rural population. In particular, between the poor, semi-proletariat elements and the kulaks or rural bourgeoisie.

Because of this, the Bolsheviks needed to win over the peasantry in general – in other words they needed to win over all sections of the peasantry, including the peasant bourgeoisie. Reflecting on this approach in the early months of the Revolution, Lenin wrote:

“…if the Bolshevik proletariat had tried at once, in October-November 1917, without waiting for the class differentiation in the rural districts, without being able to prepare for it and bring it about, to “decree” a civil war or the “introduction of Socialism” in the rural districts, had tried to do without a temporary bloc with the peasants in general, without making a number of concessions to the middle peasants, etc., that would have been a Blanquist distortion of Marxism, an attempt of the minority to impose its will upon the majority; it would have been a theoretical absurdity, revealing a failure to understand that a general peasant revolution is still a bourgeois revolution, and that without a series of transitions, of transitional stages, it cannot be transformed into a socialist revolution in a backward country”.

In order to win over the peasantry, the Bolsheviks formed a coalition with the Left Socialist Revolutionaries (Left SRs) – a peasant party which split with its right wing in October/November 1917. Together with the Left SRs the Soviet Government made the first Decree on Land at the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers and Soldiers Deputies in October/November 1917.

This Decree was a bourgeois, anti-feudal (i.e., non-socialist) measure which included provisions on the nationalisation of land, the confiscation of landed estates and the equal redistribution of land to the peasantry.

The accompanying Peasant Mandate on Land also forbade confiscation of peasant land and saw the transfer of control over land to Volost Land Committees and Uyezd Soviets of Peasants Deputies. This second measure meant that political power in the countryside and control of the semi-feudal estates was transferred to the peasant soviets.

What followed in these first months was a general peasant revolution against the landed aristocracy. In the Summer and Autumn of 1918 (June-July) however, class differentiation between the different sections of the peasantry began to emerge and class struggle broke out in the rural districts. This is explained by Lenin:

“The Czechoslovak counter-revolutionary mutiny roused the kulaks. A wave of kulak revolts swept over Russia. The poor peasantry learned, not from books or newspapers, but from life itself, that its interests were irreconcilably antagonistic to those of the kulaks, the rich, the rural bourgeoisie”.

At the Eighth Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolshevik) in March 1919, Lenin presented the Report On Work In The Countryside in which he said,

“…the real proletarian revolution in the rural districts began only in the summer of 1918. Had we not succeeded in stirring up this revolution our work would have been incomplete. The first stage was the seizure of power in the cities and the establishment of the Soviet form of government. The second stage was one which is fundamental for all socialists and without which socialists are not socialists, namely, to single out the proletarian and semi-proletarian elements in the rural districts and to ally them to the urban proletariat in order to wage the struggle against the bourgeoisie in the countryside. This stage is also in the main completed.”

To summarise, the Bolshevik Revolution occurred over two, interrelated stages. The first stage was characterised by Lenin as, “with the “whole” of the peasantry against the monarchy, against the landlords, against the mediaeval regime… [a] bourgeois-democratic [revolution].”

The second stage took place in November 1918 when class struggle broke out between the rich peasants and the poor peasants. This second stage was characterised as, “with the poor peasants, with the semi-proletarians, with all the exploited, against capitalism, including the rural rich, the kulaks, the profiteers, and to that extent the revolution becomes a socialist one”.

A key feature of this second stage was the transfer of power from the peasant soviets to Poor Peasants’ Committees. To assist this process, 40,000 armed workers were sent to the countryside. In his 1998 essay Trotsky’s theory of permanent revolution: A Leninist critique, Doug Lorimer provides a succinct overview of the realisation of Lenin’s two stage theory of revolution in Russia:

“…in the Bolsheviks’ view, the October Revolution – as it had unfolded in the year after the insurrectionary seizure of political power in Petrograd on November 7, 1917 – had confirmed the correctness of their policy of carrying out the proletarian revolution in Russia through two stages.

During the first stage, which lasted up to June-July 1918, the Russian working class transferred political power in the cities to the workers’ soviets and other organs of proletarian state power. The urban proletariat was only able to do this because it forged a political alliance with the peasant masses, who, during this same period, transferred political power in the countryside and control of the semi-feudal estates to the peasant soviets.

During the second stage of the October Revolution, from July to November 1918, the urban workers used the state power they had seized and consolidated in the cities during the first stage to forge an alliance with the semi-proletarian majority of the peasantry against the urban and rural bourgeoisie. Some 40,000 armed workers went into the countryside to help the poor peasants organise themselves independently of the rich-peasant dominated rural soviets, to confiscate the surplus grain, land, animals and tools of the rich peasants and to bring the rural soviets under the control of the poor peasants and agricultural workers.

Thus, the October Revolution began as a worker-peasant democratic revolution and, then, eight months later, developed uninterruptedly into a proletarian-socialist revolution. It was the continuity of proletarian political leadership that gave the transition from the bourgeois revolution to the socialist revolution its uninterrupted character, i.e., made them two stages of a single, uninterrupted revolutionary process.”

Summing up of Bolshevik tactics in 1917-1918 and Lessons for Today

An earth-shattering lesson of the Bolshevik Revolution was that it proved proletarian state power could be won in an “industrially backwards” country through an alliance of the working class and peasantry, to be led by the former.

Having completed the ‘bourgeois’ phase of the revolution and established a “revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry”, the proletariat would be in a position to ally with the rural semi-proletariat and lower strata of the peasantry to carry out a socialist revolution. While the first phase would destroy the semi-feudal autocracy, the second would sweep away capitalist social relations.

This had far-reaching ramifications in the battle for socialism outside the imperialist core. In the Vietnamese context, Allen Myers writes, “Under Ho Chi Minh’s leadership, the Vietnamese Communist Party succeeded in applying Lenin’s strategy to the concrete conditions of Vietnam and thus leading the workers and peasants of that country to victory”. Indeed, Vietnamese revolutionary leader General Vo Nguyen Giap wrote in 1959,

“Vietnam was a small, weak, colonial and semi-feudal country, covering a fairly small area, with a small population and an extremely backward agricultural economy. There was struggle of the people throughout the country, under forms of armed uprising and long-term resistance to overthrow imperialism and the reactionary feudal forces. The aim was to realise the political goals of the national democratic revolution…to recover national independence and bring land to the peasants, creating conditions for the advance of the revolution of our country to socialism” (See: People’s War, People’s Army).

Revolutions in the Global South after WW2 – in Vietnam and elsewhere – unfolded in a distinctly two-stage process. Revolutionaries first set about completing the democratic tasks of the revolution – such as national independence and agrarian reform – in order to mobilise masses of people against imperialism and its most reactionary agents.

Once these enemies had been overcome, it was then possible – based on both subjective and objective factors – to embark on a higher stage of the revolution. In the context that existed at the time – where a victorious revolution could expect support from the Soviet Union – this could include full expropriation of the capitalist class and the establishment of a nationalised, planned economy.

Revolutions that have occurred since the collapse of the Soviet Union – such as in Venezuela – have not had available to them the favourable trade terms and aid from the USSR that was indispensable to earlier revolutions, such as Cuba. In this new context it is not possible for revolutions in small Global South countries to rapidly move to expropriate the entire capitalist class.

They remain stuck for a long period of time in the first stage and all the contradictions associated with it. For socialists – particularly in the imperialist countries – that fail to understand the objective conditions for Global South societies within the imperialist global system – the only thing holding them back is that the leadership is wrong.

As well as a departure from sectarianism, what is needed today is an approach that seeks to develop a concrete understanding of the contradictions, nature and realities of revolution outside the imperialist core.

This analysis must be combined with an unswerving commitment to solidarity with revolutionaries in the Global South in the struggle against imperialism.